← Previous

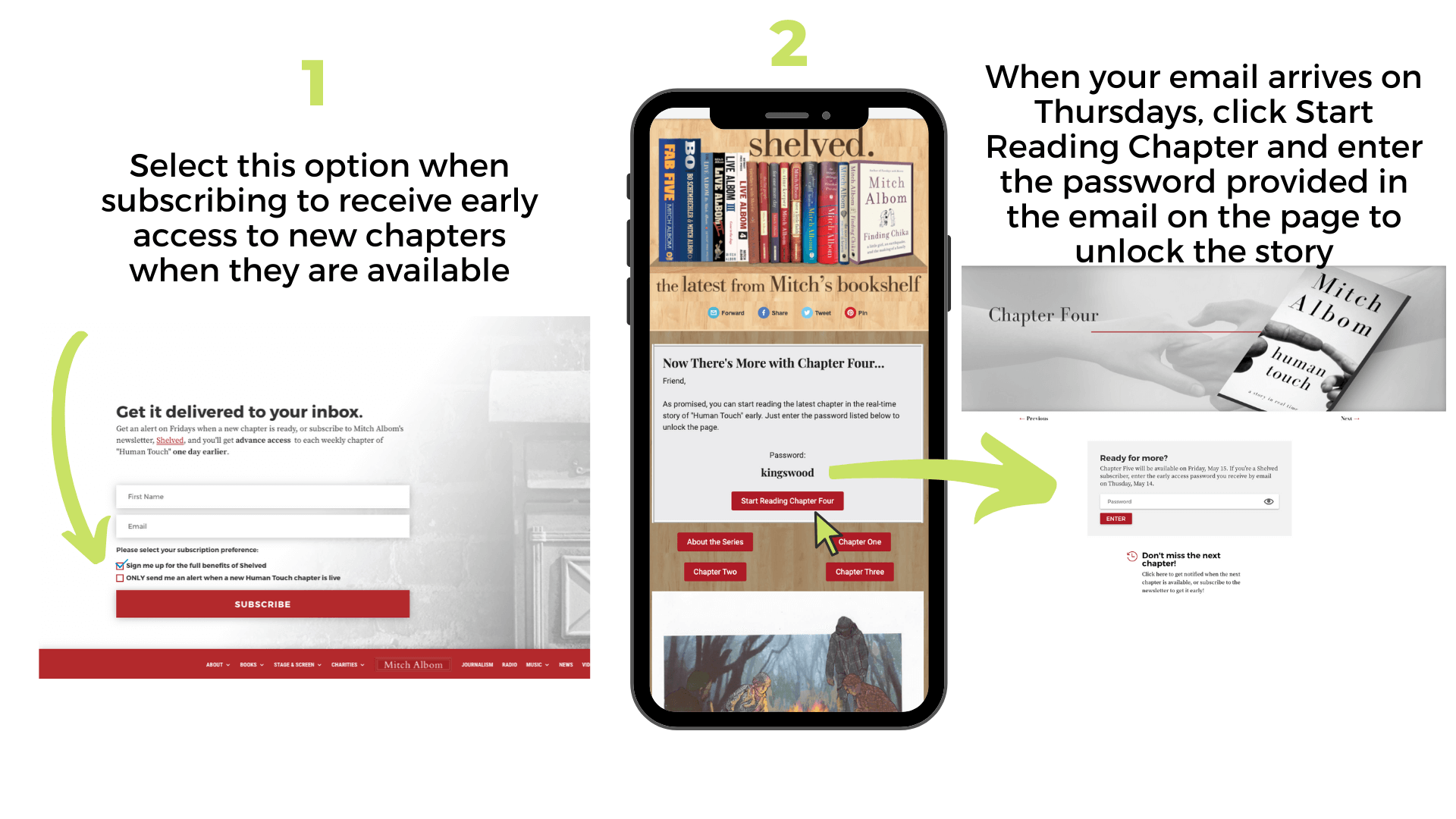

Home →

Need to Catch Up?

If you’re just getting started or need a refresher, click the link to watch a recap

Week Thirteen

Aimee steers her car into the Pleasant Ridge assisted living center. Her mother, Ginger, points out the window.

“Park near the door,” she says.

A few minutes later, they are waiting outside the entrance, standing by the curb in the hazy midday sunshine. Ginger is leaning on a cane.

It feels so strange to be back, she thinks. The last time she was here, three months ago, Aimee was packing her up and insisting she come live with them. They left in a hurry. That was before Ginger got sick, before she nearly died from the virus, before she miraculously recovered.

“Oh, look, there’s Felicia,” Ginger says.

A nurse wearing a mask and gloves walks out a sliding glass door.

“Hi, Felicia!” Ginger says, waving.

“Ginger,” Felicia says, stopping a good distance away. “It’s so good to see you.”

“You look tired,” Ginger says.

“Mom,” Aimee whispers.

“It’s OK,” Felicia says, forcing a smile. “She’s right. We’re all putting in long shifts. It’s hard to get people to work now. A lot of the staff left.”

Ginger squeezes the handle of her cane. They had to call ahead and make an appointment even to stand outside. She was not allowed into the place. Not allowed in? It had been her home for two years.

“How is Sylvia?” Ginger asks.

“Sylvia…is in the hospital,” Felicia says. “She’s been there for a week. We’re hoping for a turnaround.”

“I’m sorry to hear that,” Aimee says.

“What about Ruth?” Ginger asks.

Felicia squeezes her lips. “She’s gone, Ginger. We lost her at the beginning of May.”

“What about the gals I play bridge with? Dorothy? Betty? Maria?”

“Maria is fine. I saw her this morning.”

Ginger waits for news on the others. Felicia raises her hands to her chin.

“I’m sorry. We’ve been hit really hard…”

“Wait,” Ginger says. “Are you saying—”

“Mom, we should go,” Aimee says, putting an arm around her shoulders.

“Go?”

“Yes, Mom. Come on.”

Ginger is stunned. She stares at her daughter as if trying to understand the language she is speaking.

“We’ll come back another time,” Aimee whispers. “I promise. But for now, please, Mom. OK?”

“All right…” Ginger says.

“Again, I’m so sorry,” Felicia says. “I’m happy to see you’re OK, Ginger. Please be careful.”

Ginger sees Felicia is crying.

“Goodbye,” Ginger mumbles, turning away. She takes small steps with her cane, as her daughter guides them to the car.

Ginger is quiet much of the ride home. Finally, when they reach the house, she speaks.

“Aimee?”

“Yes, Mom?”

“I want to know what Greg did to me.”

“What do you mean?”

“I want to know why I am alive and all my friends are not.”

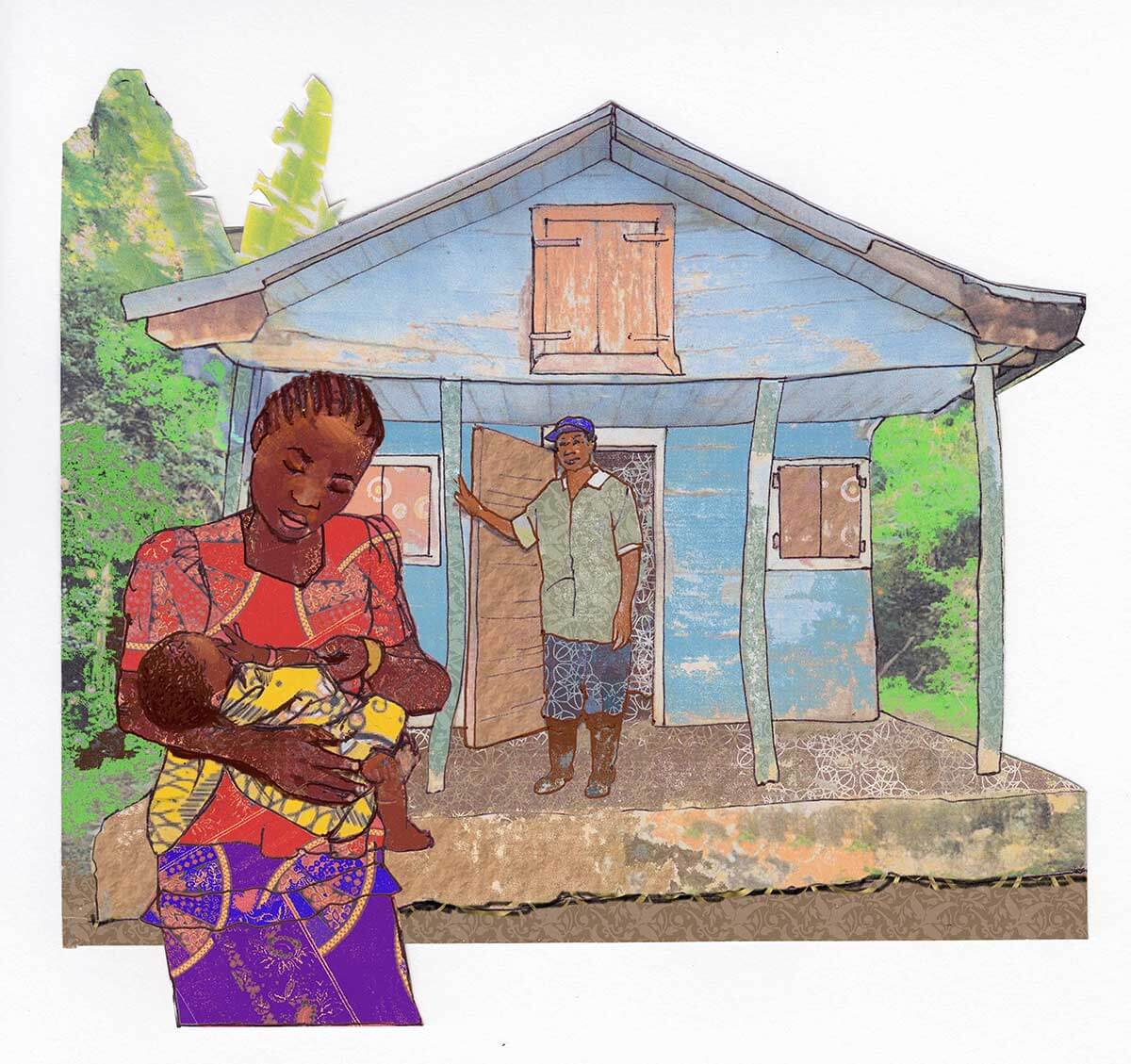

ROSEBABY SNEAKS into the back of the church. She knows no one will be there at this time of day. Pastor Winston is still fighting the virus at home and Lilly is tending to him.

Rosebaby carries two sandwiches in a plastic bag. She knocks on the door marked “Choir.” She waits five seconds, then pushes inside. She sees the Haitian man in the cap and earring sit up on the couch where he’d been sleeping.

“Koman ou ye?’’ she says. How are you?

“I am quite well, thank you, Rosebaby,” he says.

“You are speaking English?”

“Well.” He smiles. “We are in America.”

Rosebaby hands him the bag.

“Here. Ou dwe manje.’’ You must eat.

“What is it?”

“Tuna salad sandwich,” Rosebaby says. “I did not have time to make something more familiar.”

He smiles.

“Tuna sa-lad sand-wich,” he says.

Rosebaby sits in a folding chair. She sees the choir robes hanging on the wall. How long it has been, she thinks, since there was any singing in this church? Or any services? Months? What good is an empty church to God? she wonders.

“You cannot hide here long,” Rosebaby says.

“I do not intend to hide,” the man says.

“Oh? Then what do you intend?”

He bites into the sandwich. He closes his eyes as he chews.

“Is good,” he says.

“What do you intend?” Rosebaby says again.

The Haitian man swallows and puts down the sandwich. He fixes his gaze on Rosebaby’s face.

“Ask me the real question, Rosebaby.”

Rosebaby stares back.

“Is Moses truly your son?”

“Yes.”

“Then why did you let me take him eight years ago? Why did you not say something when I brought him to you from the woods?”

The man rubs his palms on his pants. He exhales, then begins his story:

“I had a wife once. Her name was Ninot. She was lovely and gentle and devoted to bringing us a family. We had three daughters. When she said that was enough blessing from God, I accepted it. But inside, I wanted a boy to carry on my name. I prayed for it every day.

“Finally, many years later, when our daughters were grown, Ninot became pregnant again. We were old to be parents. But we were grateful. Ninot gave birth in the river. Hard births, I am told, are made easier that way. When our son was born, we named him Moses, because the word means to draw something from the water, and indeed, that is how he came into this world.

“For the first month of his life, Ninot and I stayed together, tending to the baby. Then one day, I returned to the village where you met me, where I practiced my healing for the nearby people. I saw some villagers who were sick. It took time. When I arrived home, it was late. Ninot had made a soup from berries she had found on a walk, but I was too tired to eat, so she finished her soup and fed the rest to Moses. Then we went to sleep.”

He pauses.

“When I woke up the next morning, Ninot was dead.”

Rosebaby puts a hand to her mouth.

“O, Bondye,” she whispers. Oh God. “What happened?”

“The berries were poison,” the man says. “I recognized that when I found them that morning. But it was too late. Moses had eaten the soup as well, so I knew he would not survive. He was still breathing, but I could not wake him. His time was near.

“After all those years of waiting for a son, to lose him just hours after I lost Ninot was too much for me. I could not bear the pain. So I took Moses to the woods, and I placed him under a tree, with a candle to light his way when he crossed over into the next world. I said a prayer…”

He looks away.

“And may God forgive me, I left him there to die.”

Rosebaby is stunned.

“But he did not die,” she says. “When I found him he was…fine.”

The man nods slowly.

“That is when I knew,” he says.

“Knew what?”

“That he was a miracle. And you were meant to be his new mother.”

“I AM HUNGRY, please,” Little Moses says.

“Give him a candy bar,” Anthony says.

“I only have three left,” J.P. says.

“Jesus, J.P, just give him a frickin’ candy bar!” Riley says.

The four of them are riding in an old Chevy Tahoe, which is pulling a small boat behind it. Anthony and J.P are up front, Riley and Little Moses are in the back. They are heading to Port Huron, a city northeast of Detroit, hard on the St. Clair River and so close to Canada you could swim across.

“Turn on the news,” Anthony says.

Riley fiddles with the radio. They listen to a story about an auto plant that, after being closed for three months, had to shut down immediately after re-opening, due to a return of the virus. Then there is a story about major league baseball deciding to postpone its season again, after three players tested positive during an exhibition game. Then a story about how a third of the country is jobless, and how the latest death projections suggest more than 300,000 Americans will die by the end of the year and close to a million will be dead world-wide.

And then: “The assault/kidnapping of a local Chinese American and a young Haitian boy has taken a new turn. According to police, the kidnappers are now demanding $10 million dollars in exchange for the boy, who was seen in a photo that is circulating the internet, with a cryptic note that reads: “We know you need him.” Police so far are not saying anything about the identity of the kidnappers or their motives, only that they reportedly are white males, in their 20s or 30s. Anyone with knowledge about the case is asked to contact the local police immediately.”

“Whoo-hoo!” Riley exclaims. “They still don’t know who we are!”

“They said three white guys in their 20s or 30s,” Anthony snaps. “That’s pretty specific.”

“Who’s in their 30s?” J.P. says. “Not me or Riley. Only you, old man! Ha!”

“Why do they have to say ‘white’ guys?” Riley says. “It’s racist.”

“Yeah,” J.P. adds. “They wouldn’t say three black guys—”

“Shut up,” Anthony interjects. “Doesn’t matter. The word’s out now. They’ll come up with the money. They need this kid.”

“You better pray you’re right,” Riley says.

“I can pray with you,” Little Moses interjects.

They all go silent. Riley looks at the boy.

“What?” he says.

“I know how to pray. Every day I do. Listen. Our father, who art in heaven, ‘allowed be the name—”

“OK, quiet—”

“Thy kingdom come, thy will be done–”

“Enough–”

“On earth, as it is in heaven—”

“If you don’t shut up, I’m gonna smack you!”

“Give us this day, our daily bread–”

“Hit him!–”

“Forgive us our trespasses—”

Riley raises the back of his hand, about to swipe.

“As we forgive those who trespass against us.”

He drops his hand.

“What’s your problem?” J.P. says.

Riley swallows. Something about those words. “As we forgive those who trespass against us.” Little Moses gazes up at him. He never looks scared, Riley thinks.

“For piss sake, I’ll smack him!” J.P. yells.

He leans over the front seat with his palm raised, but Little Moses dives quickly into Riley’s shoulder, and the blow only grazes him and follows through into Riley’s neck.

“Hey, moron!” Riley yells. “Watch it!”

“Just…shut up!” J.P. yells, staring at Little Moses.

J.P. returns to his seat, grumbling. Riley looks down and realizes his arm is around Little Moses, as if protecting him.

“Five minutes to the exit,” Anthony announces.

Week Fourteen

On Saturday morning, four cars leave the four houses on the corner. They travel north for 20 minutes and park on the outskirts of a heavily wooded lot.

One by one, the doors open, and the families get out. There’s Greg and Aimee and Ava. There’s Sam and Cindy. There’s Old Man Ricketts, Charlene, Buck and Daniel. And finally, there’s Lilly, who has driven herself; Winston is still sick.

“This is the place?” Ricketts asks Buck.

“I don’t know exactly,” Buck says. “It was dark. I can’t remember.”

“This is it,” Daniel says. “I came in on the other side, where there’s a driveway. The house is over there. We just have to climb the hill to see it.”

“Then that’s what we do,” Ricketts says. He turns to the others. “Pair up and fan out.”

The neighbors have decided to make this journey, to explore a hunch, because the authorities have been unable to locate Little Moses. He’s been gone almost two weeks.

So much has happened since the night Little Moses was taken. Men from the government had followed Greg home after work, and interviewed every family on the block. They grilled Sam about the attack and asked him why the men would take the boy if Sam was their target.

“I don’t know,” Sam said.

They confronted Rosebaby about the vial of Little Moses’s blood she had provided to Greg. When she left the room and returned with eight more vials, she noticed the look on the men’s faces. They seem more interested in the blood than Little Moses himself.

Meanwhile, Ricketts had learned all about Buck’s time with Riley, J.P. and Anthony — or as Ricketts called them, “The wanna-be militia.” When Daniel heard Buck describe the men, he blurted out, “Holy crap! I think I brought those guys a pizza! They had a gun on the floor!”

The police were dispatched to the cottage, but they came back saying it was abandoned. A “dead lead” they called it.

“I’m telling you they were there,” Daniel told his grandfather.

On Friday night, just after dinner, the families had walked down to their respective corners and held a long conversation in the street, often shouting to be heard. The sun stays out late on Michigan summer nights, and at times it felt more like an afternoon summit. Everyone had something to declare.

“We can’t just sit around here!” Ricketts said.

“How do we know the police are trying their hardest?” Aimee said.

“We don’t,” Greg replied. “After the feds got that blood from Rosebaby, for all we know, we won’t hear from them again.”

“We’ve always looked out for each other,” Lilly said. “I know this sounds corny, but I always felt, in some ways, you were kind of our family.”

“Me, too,” Aimee said. Others nodded.

“Then we have to do what a family does,” Lilly said.

“What’s that?” Greg said.

“Take things into our own hands,” Sam declared.

“Take things into our own hands,” Ricketts echoed.

The two men looked at each other.

“Sam, I owe you an apology,” Ricketts said. “When this whole thing started, I acted like you somehow did something to bring the damn virus here. That was just stupid.”

“Yes, it was,” Charlene said.

A few laughs.

“You didn’t have to agree that fast, Charlene,” Ricketts said.

More laughs.

“Look,” Sam said, “Mr. Ricketts—”

“Pete.”

“Pete.”

“The fact is, if you didn’t bandage me up the night I got shot, I’d have been in much worse shape. You kind of saved me…Pete.”

Cindy took her husband’s hand.

“Yes, thank you, Pete,” she says.

The others smiled.

“So you won’t move away on us?” Ricketts said.

Sam and Cindy looked at each other.

“I don’t know,” Sam said.“There’s a lot of intolerant people here.”

Cindy put her arm around him. “But a lot of pretty decent people, too.”

The families looked at one another across their four corners. At that moment, the sweep of all they had been through these last three months seemed to drape over them, pulling them closer. They were more than neighbors now. The crisis had made them a community.

“Ah, hell, what would we do in San Jose?” Sam finally said. “They don’t get the Lions games out there.”

Greg laughed. He began clapping, slowly, until all the others clapped along. The applause went on for at least a minute, until Sam actually smiled and said, “OK, OK.”

Before returning to their homes, the families agreed: they would investigate the cottage for themselves.

NOW, SATURDAY MORNING, they walk slowly up the hill, two by two, looking through the leaves.

Ava is walking with Daniel.

“Hey, I forgot to tell you, I saw Troy a while ago,” Daniel says.

Ava looks at her feet.

“Oh yeah?” she says. “What did he want?”

“He was asking if I saw you.”

“What did you say?”

“I said I always saw you when the families got together. You know, like for fun activities like this.”

They both laugh.

“He also — well, I shouldn’t probably tell you this—”

“Go ahead,” Ava says, “It won’t change anything.”

“He didn’t want you to know how bad he looked when he was sick. He told me to tell you he looked studly.”

“Why didn’t you?” Ava asks.

Daniel shrugs. “I dunno.”

Ava kicks at a pile of leaves.

“It doesn’t matter. We’re not a thing. He never even bothered to call to see if I was OK after he got the virus.”

“You’d have to be pretty close to him to catch it,” Daniel says.

“Yeah, well,” Ava says, not finishing.

Daniel looks at her. “Oh,” he says.

“It’s nothing. It’s not a thing. We’re not a thing. He’s just… a jerk.”

They continue climbing the hill.

“I’ve known you a long time, huh, Ava?”

“Uh-duh!” she says. “Since we made snowmen together in third grade.”

Daniel laughs. Then, without looking up, he says, “The reason I didn’t tell you is because…I didn’t want to talk to you about some other guy looking studly. Y’know?”

Ava digs her hands in her pockets and smiles.

“Yeah, I know.”

TWENTY MINUTES LATER, Ricketts yells, “Hey, Hey!” and waves his arms. “Everybody gather in!”

The neighbors converge near the top of the hill.

“There it is,” Ricketts says.

He points to a cottage, off in the distance, and a long driveway leading to the main street, just as Daniel had remembered.

“Should we all go down there?” Aimee whispers.

“Not all of us,” Ricketts says. For the first time Aimee notices he’s wearing a holster holding two guns under his jacket. He takes one gun out, holding it sideways.

“Sam,” he says, turning Sam’s way. “You were in the service, right?”

Sam takes the gun.

“Let’s go,” he says.

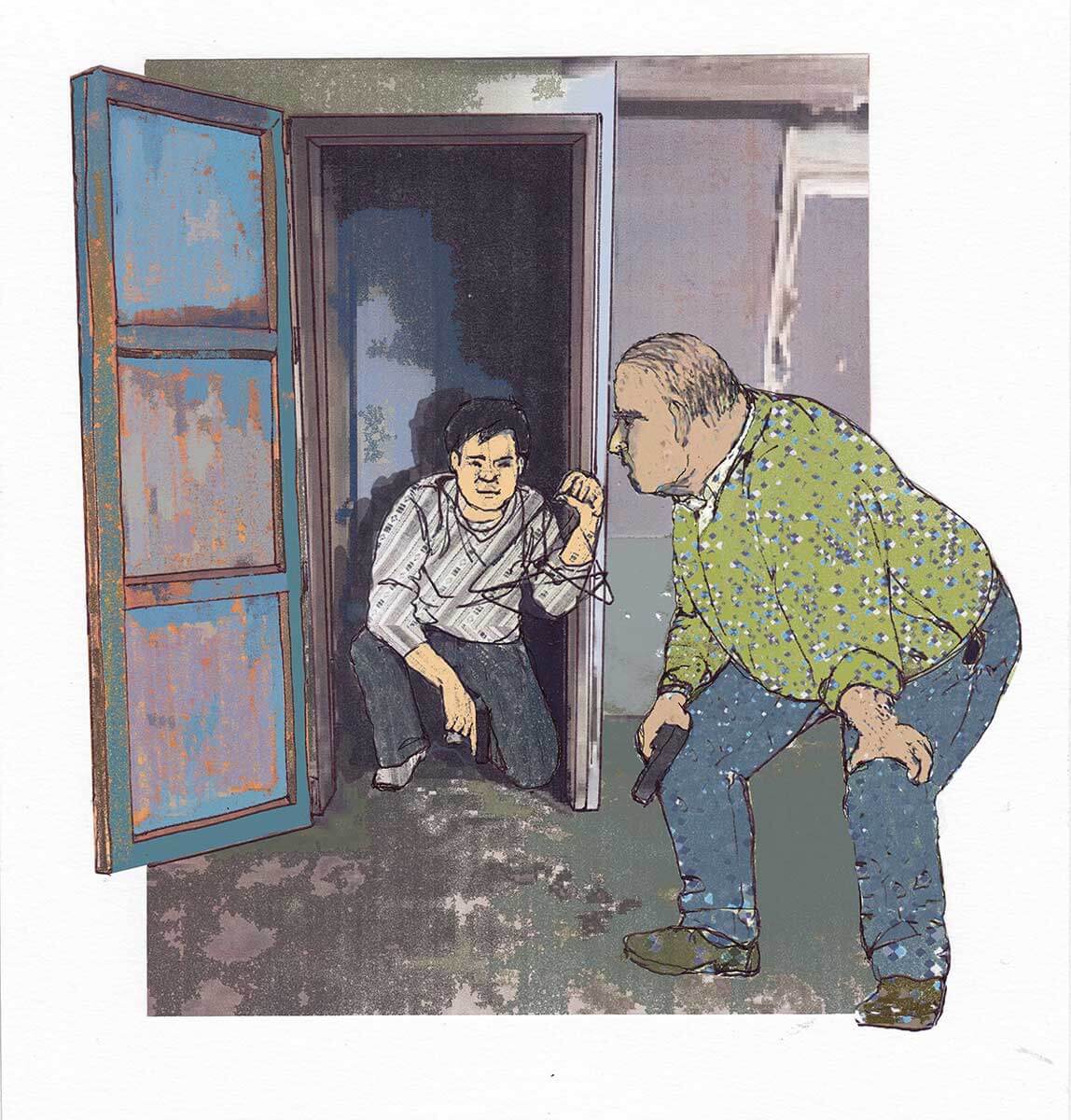

A few minutes later, Sam and Ricketts are inside the empty cottage. The police were right. It’s abandoned. No one has been here for a long time, or so it seems. There are some old clothes over a chair, some empty pots with dried macaroni on the bottom, some wrappers from candy bars.

Sam opens a closet. He looks down and feels a tingle run up his back.

“Hey!” he yells.

Ricketts darts into the room. Sam is on the closet floor.

“This is mine!” he says, holding up a black glove. “I gave it to Little Moses when we were going out that night, so he could hold the sign without getting splinters.”

“He was here?” Ricketts says.

“And look at these,” Sam says.

He picks up three wire hangers. They have been twisted together into some kind of toy, two triangles and a curved bottom.

“Moses plays with hangers at our house. Cindy always tells him not to, because we need them for clothes, but…”

“What is it?” Ricketts mumbles.

“It’s a boat,” Sam says. “See the sails?”

“You think it means something?”

“I don’t know. He always says he likes cars and trucks.”

“Then why would he make a boat for himself?”

Sam looks down. He fingers the hangers.

“What if he made it for us?”

PASTOR WINSTON lies on a couch in his basement. There’s a bowl of soup and toasted pita on a tray. He hasn’t touched it. He has no appetite. His arms and legs feel so stiff, it’s as if there are wooden planks inside them. His eyes hurt, his head is throbbing, and his chest feels like an anvil is resting on top of it. He can only take half breaths before needing to exhale and inhale again.

Todd, his oldest child, is at the top of the steps, talking on a cellphone.

“OK, Mom…I will…” he says. He yells down to Winston. “Mom says they’re on their way back.”

“Good,” Winston says, his voice scratchy.

Todd hangs up but remains on the top step, his chin in his hands.

“Are your sisters all right?” Winston asks.

“Yeah. They’re playing upstairs.”

“Todd?”

“Yeah?’’

“How are you doing? You know, with all this?”

Todd makes a face. “OK, I guess. I just want you to get better. And I want everything to go back to normal. I kinda miss school. I liked things the way they were.”

“Things don’t always stay the way they were.”

“I know,” Todd says, looking down. “You always say that.”

Winston grabs a tissue and wipes his nose and mouth.

“Can I share something with you?” he says.

“What, like a sermon or something?”

Winston laughs softly, although it hurts. “Maybe half a sermon.”

Todd leans back, still holding his phone. “OK, Dad. Go ahead.”

“You know your Bible. So you know the book of Job, right?”

“Yeah. He’s the guy who has a good life then has everything taken away by God. As a test.”

Winston nods. “Yes…yes…very good. And after he loses everything, his money, his family, his health, Job finally breaks down. But he still believes that God can do what God wants to do, and man should never doubt Him. He says this line, if I remember it right:

“My ears had heard of you

but now my eyes have seen you.

Therefore I despise myself

and I repent in dust and ashes.”

Winston swallows hard. “I felt a little like that, Todd. I insisted on holding those services, because I didn’t want anyone telling us when our congregation could assemble. It was as if only my ears could hear God. I was sure I was being righteous and those warning me were not.

“Then I found out our members had gotten sick. And then Charlene Laughlin…died.”

He struggles to get his breath. He pushes on.

“I despised myself. Like Job. I wanted to repent. So I went to the quarantine shelters in Detroit, and I fed patients their meals.”

Todd interrupts, his voice suddenly angry. “That’s where you got sick. Why did you go there? You didn’t have to go there!”

Winston takes another tissue.

“I did have to go there, Todd. When a man of faith loses his way, acts of service are the light that guides him back.”

“You went there to get sick!” Todd says.

“No, sweet boy,” Winston says, gently. “I went there to get better.”

Todd begins to cry. “But you’re sick now. You look so sick, Dad.”

Winston exhales hard. His head is pounding.

“Don’t cry, Todd. Do you know what happened after Job said those words to God? Therefore I despise myself and repent in dust and ashes?”

Todd shakes his head.

“God gave Job everything back. In fact, he gave him twice as much as he had before.”

“Is that what’s gonna happen to you?” Todd says, half-laughing and half-crying. “The church is gonna be twice as big?”

Winston pushes up a smile. “Right now, I’ll settle for feeling better. And you know what? Talking to you, I do.”

Winston struggles to lift into a sitting position. He looks at his son on the top step, just 11 years old, trying to make sense of this new world.

“Long distance hug?” Winston croaks, holding his arms out in an invisible embrace.

“Long distance hug,” his son replies, lifting his arms and tapping off the red button on his phone, which had been recording everything his father said.

LITTLE MOSES IS dreaming again. He had squeezed his eyes shut after they locked him in the car, and he said to himself, “I am Flash, I am Flash, I am Flash” until he fell asleep.

In his dream, he is running again in the clouds. Up ahead he sees the Haitian man with the hat and the earring. This time the man is sitting down, crouched over a small fire. He seems to be holding something in his hands. Little Moses runs around him making a zooming sound.

“I cannot see you, Little Moses,” the man says.

“That is because I am too fast,” Little Moses replies. “I am Flash!”

“Can you slow down for me?”

“No! Flash cannot go slow!”

Little Moses makes a few more passes, then, realizing the man will not play with him, he ceases running.

“I am stopped,” he says.

“Thank you,” the man says. “Come closer.”

Little Moses tries, but suddenly he feels very tired. He lies down.

“Are you with the man with the deer hat?”

“Yes,” Little Moses says, yawning. “I run away like you told me. But they catch me.”

“Did they hurt you?”

“They only catch me because I do not have my Flash clothes on!”

“Did they hurt you?”

Little Moses rolls over. “They hit me.”

“Eske ou fe byen kounye a?” Are you all right now?

“Oui,” Little Moses says. “Mwen fatige.”

“I know you are tired, Little Moses, but I need you to stay a little bit awake, all right? I cannot see you. Can you lift yourself up?”

Little Moses likes the way the clouds feel. He doesn’t want to move.

“I am tired,” he says again.

“Your mama wants you to lift up,” the man says.

Moses stirs at the word.

“Mama?” he says.

He pushes his torso up from the clouds. The wind begins to blow, silently, and the mist starts to thin. Little Moses blinks his eyes and sees a string of blue lights above a body of water and something that looks like a long bridge.

“Ah,” the Haitian man says, looking over from the fire and smiling with his missing teeth, “there you are.”

GREG PULLS INTO the parking lot of the hospital. It is dark and the lot is largely empty. He swigs what is left of the coffee he made before leaving the house. He is scheduled to work until 7 a.m., but after the day he and his neighbors had, he’s not sure how he’ll make it through the night.

Before he can get down the glass corridor that leads to the main building, Carl, the virologist, comes running his way. He’s pushing his hands forward as if to signal, “Go back!’’ and Greg instinctively turns and hurries back towards the garage.

Carl catches up to him, breathing heavily. “They’re waiting for you in there!’’

“Who?”

“The feds. Whoever those guys are from the government.”

“They’re back again?”

“With four cops.”

Greg’s heartbeat quickens. “Why?”

“Did you go somewhere today? Without telling them?’

“We went to look for Little Moses.”

“Well, they think you know something you’re not saying. Why didn’t you tell them?”

“Carl, I don’t even know who the hell they are! The local cops aren’t any help. We went to this cottage to try and find the kid.”

Carl grabs Greg’s arm. “You know how serious these guys are, right? They think this serum could be the answer. They’re already talking about human trials. But that doesn’t mean they trust us. They watch me all day long here. And they’re always asking when you’re coming in.’’

“Why aren’t they just grateful we gave it to them?”

“Probably because they’ve never seen anything like it. Whoever creates a vaccine for this virus changes the world. But that usually takes a couple years. If you do it too fast, it makes people suspicious.”

“So we’re suspicious now?”

“Greg?”

“Yeah?”

“They want that kid.”

Greg spots his car and Carl almost pushes him towards it. “I’m not saying a word about seeing you, OK? Make up some excuse about why you weren’t here.”

Greg nods as if memorizing instructions. He suddenly can’t get his car started fast enough.

“And don’t go home!” Carl yells.

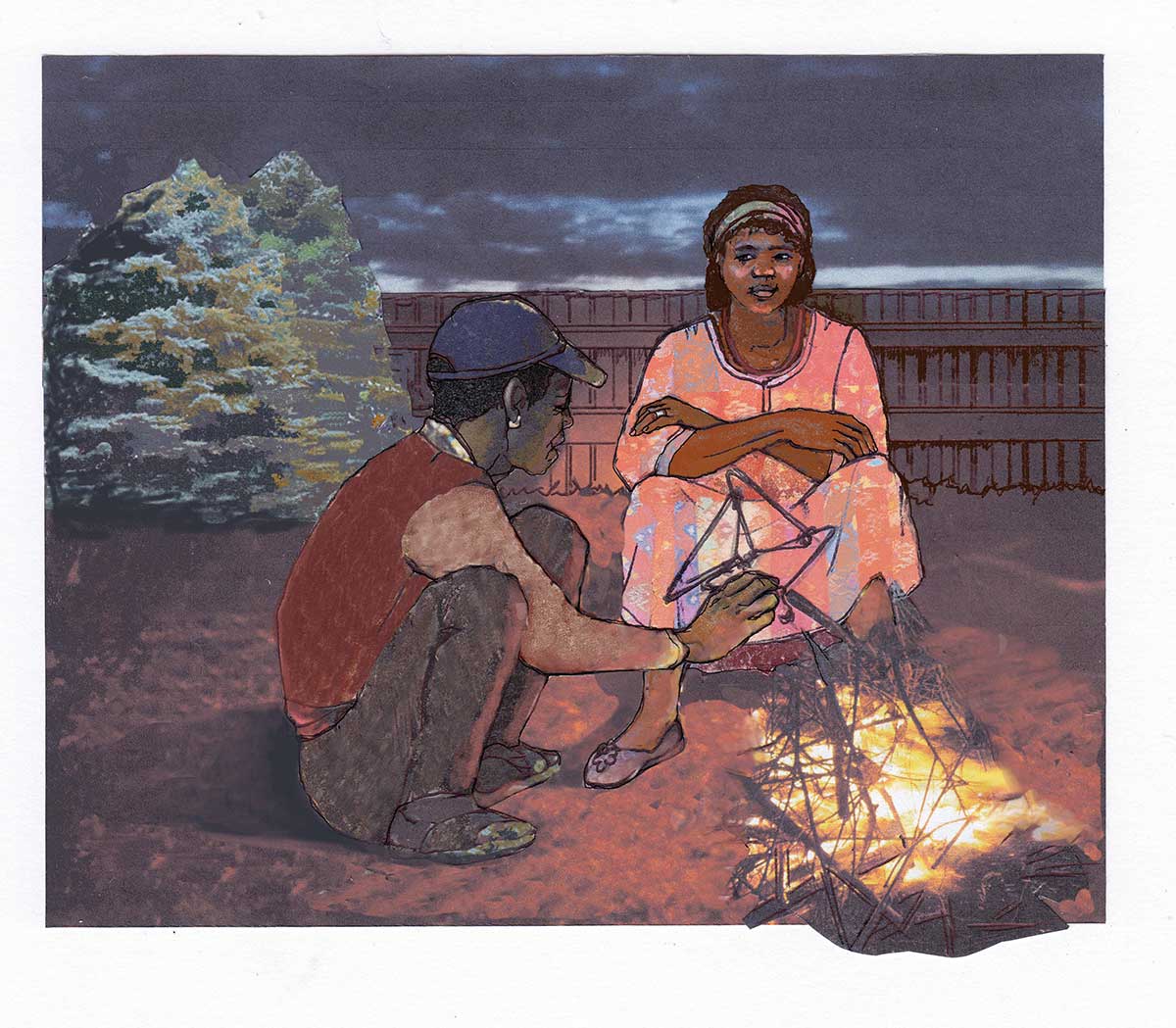

“Hell if I know,” Ricketts says.

It is 9:30 Saturday night, and they are standing with Cindy, Aimee and Charlene, spaced out across the deck that overlooks the Lee’s backyard. They are all watching this strange Haitian man, who Rosebaby introduced as “Papagee”, sitting in the middle of the yard by a small fire he built with sticks, twigs and some things he had in his bag.

Rosebaby squats next to him. Papagee holds the hangers that Little Moses shaped into a boat. Occasionally he lifts them to the sky and wiggles them as if they were an antenna trying to get a signal. All the while, his eyes are closed.

“Did Rosebaby say where this guy came from?” Aimee mumbles.

“All she told me,” Cindy says, “is that he knows what to do.”

“Have you ever seen him before?”

“No.”

“Did you look in his eyes?” Charlene says.

“What?” Cindy says.

“Something strange. Like he’s not altogether—”

Suddenly, they hear Rosebaby squeal. She falls forward and drops her head on the Haitian man’s shoulder. The neighbors run off the porch to help her.

When they reach the fire, they see Rosebaby is crying, but smiling.

“We know where he is,” she says.

“How does one get to the Blue Water Bridge?” the Haitian man says.

“You gassed it up?” Anthony asks Riley.

“Yeah.”

“You sure?”

“Jesus! Yes, I gassed it up!”

“Get the kid.”

Riley goes to the Tahoe. Little Moses is sleeping in the back seat. Seeing the boy makes Riley feel tired, and he thinks about how long it’s been since he’s had a good meal, a good shower, and a real night’s rest.

“C’mon kid,” he says, shaking Little Moses. The boy wakes up and wipes his eyes as Riley lifts him from the vehicle. Once on his feet, Little Moses reaches out and takes Riley’s hand.

“What are you doing?” Riley says, staring at the grip. The boy is still half-asleep. For a moment, Riley feels himself smiling. Human contact. He hasn’t had any since this virus began. Not a handshake. Not a hug. Not a kiss. He doesn’t pull his hand away. Instead he squeezes Little Moses’s fingers.

“Riley, let’s go!” J.P. yells.

Riley leads Little Moses along. “Come on, buddy,” he says, softly.

“What will we do now?” Little Moses asks, yawning.

“We’re gonna go in a boat.”

“Will you go with me?”

Riley feels tears forming. This kid has no idea what’s coming. Deep down Riley doesn’t believe Anthony will ever get the money. He fears he’s going to kill the kid, then kill J.P. and Riley to make sure nobody talks. There is something icy about Anthony. Some people say they don’t care. He truly doesn’t.

“OK, here’s the deal,” Anthony announces. “When we know we have the money, we leave the kid tied up, and we take the boat up river till we can find a spot to hop into Canada.”

“How are we getting the money?” J.P. says.

“They’ll wire it to an account.”

“You can’t use your bank account. They’ll trace it.”

“Not my account, you half-wit,” Anthony says. “I set up an off-shore account. Unnumbered. Untraceable. What do you think I’ve been doing on the computer all this time?”

J.P. nods, impressed. “You got the angles, brother.”

Riley looks away. He doesn’t believe any of it. Who can set up a bank account that way? How would they get out of Canada to fetch the money?

“Kid, get over there now,” Anthony says, pointing to an empty patch of grass beside the service drive that leads to the bridge.

Little Moses hugs Riley’s leg.

“I do not want to. I want to see my Mama and the man from Haiti!”

Riley feels the boy squeezing him for protection.

“Hey, Anthony, can’t we leave him—”

“Shut up,” Anthony yells. “What are you, Papa Bear all of a sudden?”

He grabs Little Moses and places him on the grassy spot, where there is no identifiable landmark in the background. He takes out his phone and snaps a photo. Then he types the words “$10 Million or 100 Pieces.”

“Now,” he says, “let’s get this kid tied up—”

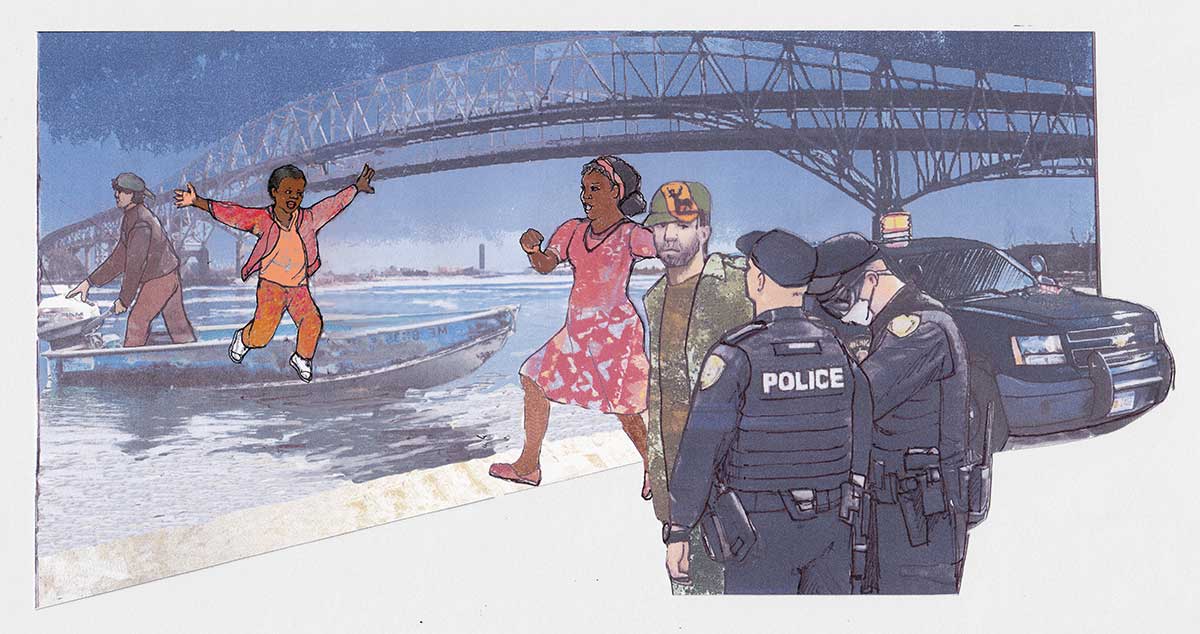

“POLICE! PUT YOUR HANDS OVER YOUR HEADS!”

Headlights flash on from two squad cars, maybe 50 yards away. Anthony grabs Little Moses and runs towards the water. He pulls out a gun. J.P. races the other way. Riley is frozen for a moment, with no idea what to do. Then he chases after Anthony. His only thought is the little boy.

A car comes screeching down the road along the water. It stops and the doors swing open. Rosebaby and Papagee jump out.

“Moses!”

“Mama!” Little Moses screams.

Papagee charges towards Anthony.

“POLICE! STOP! WE WILL FIRE!”

Anthony sees the black man in a cap running his way. He fires a shot — and is tackled by Riley, who grabs Little Moses and runs to the boat. Anthony scrambles to find his gun again, rises and fires once more at the black man, who rolls to the ground.

“POLICE! DROP THE WEAPON!”

“Moses!” Rosebaby yells.

“DROP THE WEAPON!”

Anthony spins towards the police with his hands up. Riley guns the motor and steers the boat away.

“Don’t shoot me!” he hollers. “Don’t shoot me! I’m protecting the kid!”

As the boat pulls away, Papagee lifts up and yells, “Alè deyo, Moses!”

Little Moses jumps from the boat.

“No!” Rosebaby screams.

All eyes turn at the sound of the splash. And then, in what many of the witnesses will remember differently, Little Moses rises and begins to run atop the water. His feet churn, making small splashes for six or seven seconds, before he reaches the edge and leaps into the arms of his mother and the man beside her.

Police, in the light of day, will point to the barely sunk stretch of old dock that served as footing for the boy’s unlikely escape.

Others will say that Little Moses was just too fast to sink.

Because, after all, he was Flash.

ON SUNDAY MORNING, an ambulance pulls up to the home of Pastor Winston. A medical team dressed like warriors enters the house. They go down to the basement and strap the ill man to a stretcher.

Winston’s fever has spiked overnight and he is sweating now and heaving his breath. A mask is put over his mouth and he feels the precious oxygen entering his body.

As they roll him through the living room, he sees his wife, Lilly, his twins, Devon and Didi, and his son, Todd, who is fighting to keep a brave smile on his face. They all say, “We love you” and “You’ll be home soon.”

“I’ll be OK,” Winston mumbles beneath the mask, although he’s not sure they can make out the words.

“Everyone is praying for you, darling,” he hears Lilly say. “Everyone.”

He blinks and nods slowly, but when the gurney rolls out the door, he understands what she means.

There, on his lawn, are hundreds of masked supporters, members of his congregation and people they brought with them, there’s Miss Jean, who has recovered from the virus, and the neighbors, the Ricketts family, the Lee family, the Myers family, and others, so many others, strangers who were moved to be here, thanks to a video of Winston’s “basement sermon” that his son posted last night and which quickly went viral.

Winston hears soft singing that grows louder as he is wheeled down the driveway. A hymn they sometimes do on Sundays in his church:

Where all our toils are over

Our suffering and our pain

Who meet on that eternal shore

Shall never part again

O, happy, happy place!

Where saints and angels meet!

There we’ll see each other’s face

And all our brethren greet.

As he is loaded into the rear of the ambulance, Winston gets a good look at this large, newly formed congregation, joined together in prayer, on a Sunday morning, on his lawn.

“Twice as much as before,” he mumbles to himself.

The doors close.

LATER THAT DAY, inside Sam Lee’s house, police officers, government officials and news reporters take turns speaking with members of the corner’s four families. Statements are written down. Others are recorded. Everyone must keep a six-foot distance and speak through masks. Still, the stories are told.

Buck tells police about his time with the three so-called militia members, all of whom have been arrested. Greg explains his whereabouts to government officials, who also take a keen interest in this new Haitian man “Papagee.” The man explains that Little Moses, who seems unfazed by the whole ordeal, “has endured much worse” and details the child’s unlikely survival of poison berries as a baby, which medical authorities will later determine created a “super’’ strain of B lymphocytes in his bloodstream that fought off all future bacteria and viruses.

Rosebaby has her own explanation.

“God wanted Moses to live and help others,” she tells whoever speaks with her, many of whom smile but do not write it down.

Ava and Daniel watch all this from far ends of a couch, occasionally rolling their eyes at each other. The other kids are happy to be together for once, and play a game supervised by Lilly, who keeps them a safe distance apart while constantly checking her phone for updates on her husband.

Little Moses answers more questions than he has ever answered before. He is tired from all the talking. At one point, Rosebaby pulls him away, saying, “My son must eat something.” But when she gets him to the kitchen, she leans over and says, “Are you all right, precious child?”

“Yes, Mama.”

“Are you still the Flash?”

He smiles. “Oh, yes!”

“Well, Mrs. Alley is not feeling well. Do you know her house? The one with the swings in the backyard?”

“Oh, I know it!”

“She is in the basement. There is a window.”

She cups his cheek.

“Go, little Flash. Do what God put you here to do.”

Minutes later he is racing across lawns, past a swing set, and to a ground-level window, which he pushes open. He drops to the floor with a thwock.

Mrs. Alley sits up on her mattress. An electric teapot is plugged in nearby, and a plate of half-eaten oatmeal rests on a tray.

“Are you sure this is OK, Little Moses?” she asks. “I don’t want you to get in trouble.”

“No one saw me, Miss.”

“I don’t want to get you sick.”

He stomps his sneaker to lose some dirt.

“I cannot get sick, Miss.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes, Miss. Don’t worry, Miss.”

A single tear falls down her cheek. She lifts her arms as the boy approaches.

“Thank you, Little Moses,” she whispers. “Thank you for letting me hold you.”

The boy feels the old woman’s arms tighten around him, savoring the comfort of a simple human touch.

“You are welcome, Miss,” he whispers.

Epilogue

Months later…

It is Saturday. A light snow falls, frosting the trees on all four sides of the corner. Outside the cider mill, a sign hangs on the door: “Closed until 3 pm.”

Inside the families have gathered in their new weekly tradition. The mill is large enough to safely accommodate them all, and by now, the routine of distancing is as second nature as handwashing, which everyone has done before taking their individual apple pies.

The Myers — Greg, Aimee, Ava and Mia — sit on benches by the right wall. The Ricketts — Pete, Charlene, Buck and Daniel — lounge behind the counter. Daniel throws a piece of pie crust at Ava, who swats at it and smiles.

“Ooh,” Mia coos. “Daniel and Ava, sitting in a tree—”

“Stop it, dork,” Ava says.

“Ava,” Aimee says, but she’s grinning.

The Lees, Cindy and Sam, are in chairs near the large apple press, sticking forks into a single pie. Rosebaby sits nearby, with Little Moses in her lap, his face sticky with apple filling.

“Hey, Rosebaby,” Greg asks, “do you ever hear from Papagee?”

“Sometimes,” she says. “He is back in Haiti. Do not ask me how he got there. He has ways.”

“Why do people call him Papagee?” Charlene says. “Is that like ‘Daddy’ or something?”

Rosebaby laughs. “It is Pap agee. Two words. They mean ‘Never ages.’”

Ricketts leans forward. “In that case, you can call me ‘Papa Gee Ricketts.’”

“Yeah, right, Grandpa,” Buck says, as the others laugh.

Lilly listens from the left side of the room and watches her children devour their pies. She longs for her husband so deeply at moments like these, the quiet, nothing-special moments. Nearly six months have passed since he died. She’s taken solace in the church and the safely-spaced Sunday gatherings that are customary now. Last week, after services, Todd brushed up against her and said, “I think I want to be a Pastor like Dad was.” That made her happy, even though it made her cry.

“Did you ever think you’d run the cider mill this way?” Aimee asks Ricketts. “Six feet apart? Masks? Plexiglass?”

“It won’t be forever,” Ricketts says. “The advantage of being old is that you know how short ‘long’ can be. After all that early craziness, we adjusted, didn’t we? Because that’s what people do.”

He looks around the room, everyone safe, yet still together.

“The fact is,” he says, “it works.”

Aimee looks at Greg, whose face is full of crumbs.

“What?” Greg mumbles, laughing.

“Nothing,” Aimee says. “It works.”

Cindy takes Sam’s hand. “It works,” she says.

Rosebaby nuzzles her nose into Little Moses’s hair.

“It works,” she says.

And finally, 700 miles away, in a laboratory that has been toiling non-stop on a new vaccine, guided by special blood cells from a little Haitian boy who proved mysteriously impervious to disease, a scientist races a stack of trial research down a hall. She bursts into a conference room, where a group of fellow scientists has been anxiously awaiting the results of phase III human trials.

“It works!” she announces, and the room erupts in a distinctly human sound that had not been heard in some time.

Joy.

End of Human Touch

Pay it Forward

If you're enjoying "Human Touch" so far, would you consider, if you're able, adding a human touch of your own by donating any amount to help my hometown city of Detroit battle the wave of coronavirus that is overwhelming it? Our citizens are struggling - and dying - in high numbers. "DETROIT BEATS COVID-19!" focuses on first responders, seniors, poor children and the homeless.

Thanks, as always,

Listen to the audio

Available for free exclusively at Audible.com. Read by Mitch Albom and a special guest!

Download as an e-book

Please consult your specific device’s manual for how to add one of these to your library.

There's always more to read with Shelved

Click here to keep in touch by signing up for Mitch’s free newsletter.

Recent Books

Finding Chika is a celebration of a girl, her guardians, and the incredible bond they formed—a devastatingly beautiful portrait of what it means to be a family, regardless of how it is made.

A sequel to the bestseller The Five People You Meet in Heaven, Eddie’s heavenly reunion with Annie — the little girl he saved on earth — is an unforgettable novel of how our lives and losses intersect.

Read it all Over Again…

About the Series

Chapter One

Read Now

Chapter Two

Read Now

Chapter Three

Read Now

Chapter Four

Read Now

Chapter Five

Read Now

Chapter Six

Read Now

Chapter Seven

Read Now

Get in the know.

Non-spammy. When there’s something great to share, we’ll send special updates your way. Exclusive items excerpts from a new book, signed book giveaways, books signings, and more. Learn more about Shelved here.