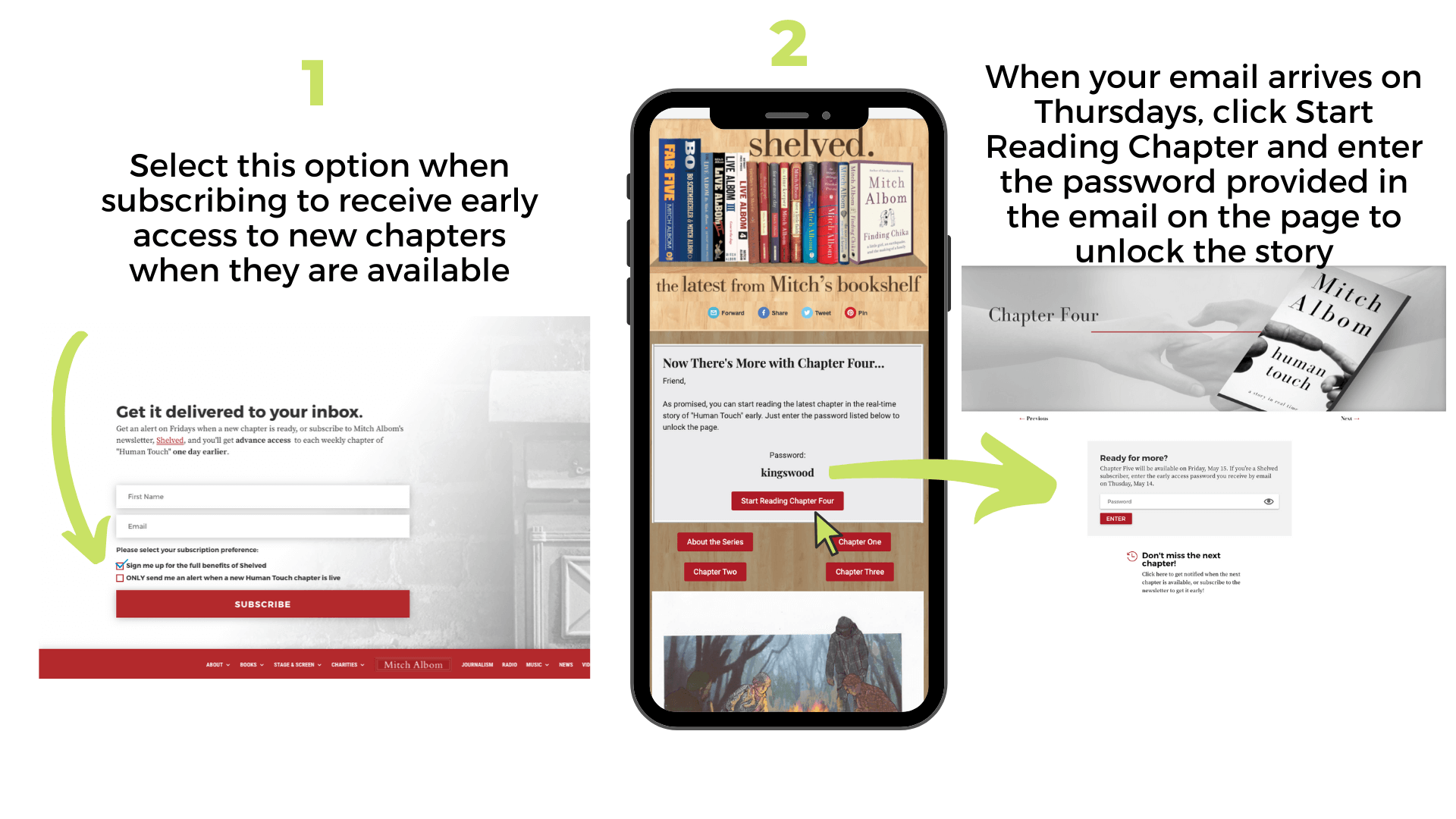

Chapter Seven

← Previous

Next →

Need to Catch Up?

If you’re just getting started or need a refresher, click the link to watch a recap

Week Eleven

Sam lies in the hospital bed, resisting the urge to touch the bandages wrapping his shoulder. A doctor enters the room, wearing a yellow gown, a respirator mask and a large eye shield that makes him look like a welder.

“So how are we doing?” the doctor asks.

“When can I go home?” Sam says.

“Well, that was a pretty nasty gunshot wound,” the doctor says. “We removed all the bullet fragments. But we want to make sure it doesn’t get infected.”

Sam snorts. He thinks about that word. “That’s pretty much the whole country now, isn’t it?” he says. “Trying not to get infected?”

“I guess so,” the doctor replies.

Sam thinks back to last Saturday evening, when he was coming out of his house with Little Moses, preparing to hammer the “For Sale” sign onto the front lawn. It had actually been a decent day. The four families from the corner had all come out for Greg and Aimee’s 20th anniversary, and they’d social-distanced their way to a celebratory gathering. It wasn’t the kind of get-togethers they used to have, with endless food and hugs and handshakes and long conversations over dinner tables. But it was nice.

And then, the attack. Who were those men? Late 20s. Scruffy. Wearing hunting caps. Their expressions somewhere between hate and fear.

“Where you going, Chinaboy?” one had said.

The rest happened so fast. There was a struggle. Little Moses raced off. One of the men pulled a gun from his coat, and Sam felt a sharp burn in his shoulder. He grabbed it and was tackled by another man, who rose and stomped on him three times, kicking his chest and stomach, screaming curses, before running after the others who were chasing Little Moses. Sam couldn’t breathe. His hand was blood-soaked from trying to stem the wound. He looked up from where he’d fallen on the lawn and saw the dimming sky and a ribbon of grey clouds. His head began to spin. And then…

“I got you, Sam, lay still.”

That voice. Gruff and weathered. Old Man Ricketts was somehow by his side, and Sam heard a ripping sound and felt his shoulder being wrapped and then the rustle of two arms beneath him as he was lifted up. He heard Ricketts say, “Hang in there, Sam, you’ll be OK,” and Sam’s head fell backwards and the world was upside down, and then everything went dark.

“Your chart says you’ve recovered from Covid-19?” the doctor says now, bringing Sam out of his memories.

“Yeah,” Sam says.

“More than two weeks ago?”

“Yeah.”

“Well,” the doctor says, “before you’re released, would you consider donating plasma?”

Sam raises his eyebrows. “You’ve got to be kidding me.”

The doctor blinks, wordless. Sam thinks about how many times he’s been called “Chink” or “Chinaman” in the last two months. He’s been spit at. He’s been shot. Shot! Anger has overtaken him. He’s gone from feeling like an ambitious, hardworking part of this country to feeling like a reduced member, an “infected” outsider. He has no affinity left for a country that could turn on him and his wife so fast, simply because of where their parents and grandparents came from. America, he feels, is nothing but boorish self-interest simmering beneath a sugary level of pleasantries. And now this doctor wants his plasma?

“Will you think about it?” the doctor asks.

“Get out,” Sam says.

BUCK WALKS along Franklin Street, past a row of stores, all of them shut down. Still, it feels good to be outside. His quarantine ended yesterday, and this morning at 8:30 he burst out the door and has been walking ever since.

He sits on a bench by a closed ice cream shop, marveling at how few cars he sees. It’s as if everyone were sucked up by some alien tractor beam. Buck plugs his earphones into his phone and watches a news update.

The virus has now infected 5 million people worldwide, and over 100,000 Americans are dead. More people are out of work than during the Great Depression. Old folks are afraid to go outside at all. No one wants to fly or take a bus. All large businesses are closed, all office buildings, all churches. They’re talking about a year or longer before anything looks like it used to look.

Buck thinks about Anthony, J.P. and Riley, the other members of the “No CV Militia” and the way they blamed this all on the Chinese, saying they invented this virus in a secret laboratory to cripple America. Maybe they were right. Who knows? Buck hasn’t heard from them since the protest at the state capitol. But they still have his grandfather’s guns.

He hasn’t told anyone that. Nor has he told anyone what he suspects: that they were the ones who shot Sam Lee. And the ones who might have taken Little Moses. Don’t say anything, he tells himself. You can’t prove it and you’ll only get in trouble. In the last two months, he’s been arrested, put in jail, banished from his house and holed up in the woods. Now, finally, he’s free to come and go as he pleases. He’s not messing that up. Not for anyone.

Buck notices a white-haired man across the street, jiggling a key and entering a barbershop. Buck has seen him before. He’s the owner. After a minute, the outside light comes on, and a neon sign that reads “Open” is illuminated.

Buck rises and crosses the street. He taps on the shop door and the white-haired man waves him in. He is in his barber’s jacket now, with a blue mask covering his mouth and nose.

“You want a haircut?” he says.

“You’re open?”

“Damn right. As of five minutes ago.”

“I thought no one was allowed to open.”

“Well, I’m not waiting for the governor or anyone else to tell me what I can do. I’m sick of sitting around. I’m 72 years old, and I’ve been making my own way since I came to this country when I was your age. I got customers who need haircuts. I got bills to pay. I’m opening. The hell with their policies. If I wait for them to say it’s OK, I’ll be out of business.”

He picks up a comb and scissors.

“You want a haircut or not?”

ROSEBABY IS on a bicycle, her tears stinging against the blowing wind. She passes a stretch of thick woods.

“Moses!” she hollers. “Moses! I am here!”

For the last four days, she has been making this bicycle ride, taking the main road from one town to the next, then crisscrossing all the side streets to insure she hasn’t missed any. It takes her from noon until sunset. Her feet are blistered from the pedaling.

“Moses! Come to me, Moses!’

Her son has been missing since Saturday evening. The men who shot Mr. Sam took him — or so the police think. They have spoken to her several times, took whatever information they needed, asked her about what he was wearing and if she had photos.

But as time passes, Rosebaby grows more panicked. She does not trust the police. In Haiti, police were of no use. If you didn’t have money or power, they wouldn’t do anything for you. She once watched the police stand by while a mob of angry bystanders killed a man, because another man said he had groped his wife. They didn’t get involved. They didn’t worry about guilt or innocence.

No. She could not trust police. She would have to find the boy herself.

“Moses!” she yells. “Please, Moses, come out!”

GREG STEERS his car into the hospital parking lot. Ten minutes later, fully dressed in PPE, he exits the stairwell onto his floor, and does a double take. There are four police officers flanking the hallway and two men in suits speaking with Carl, the virologist. Carl glances up and makes eye contact. Instantly, Greg knows Carl’s been talking about him.

“Dr. Myers,” one of the well-dressed men says, approaching quickly.

“Yes?” Greg says.

“Can we have a word?”

Greg notices the police officers moving in step, and suddenly they are all walking together, like a small parade, past the admitting stations and into the back offices. Greg enters a consultation room, followed by the two men, then the officers, then Carl. An officer closes the door.

“Can I ask, ‘Who are you?’” Greg says.

“I’m with the CDC,” the first man says. “My name is Rishi Barua.” He nods at his cohort. “Theo is with the NSA.”

Rishi hooks his hands together. “Dr. Myers, we have some questions, specifically about the subject behind this serum.”

“What serum?” Greg says.

“Greg,” Carl says, softy. “I sent it to them.”

“What?”

“It’s too powerful. We can’t keep it to ourselves.”

“I know, I just…” Greg swallows. “I didn’t know you had completed a serum.”

“The folks at our lab did preliminary work,” Rishi says. “They tell me they’ve never seen anything like it.”

“In what way?” Greg says.

“The lymphocytes. The B cells. They’re like some super strain that recognizes everything.”

“What do you mean?”

Rishi pauses.

“I mean, they killed Covid-19 in less than a minute.”

Greg looks at Carl, wondering if he shared the fact that Greg had used some of Little Moses’s blood to cure his mother-in-law. If so, his medical career is over.

“Dr. Myers,” Theo, the NSA guy, says. “Let’s cut the crap.”

Greg notices his deep voice and New England accent.

“What do you want?” Greg says.

“We want to know where this blood came from. And how we can get more. Now.”

Greg looks down.

“That’s going to be hard,” he says.

Week Twelve

“I want to go home!” Little Moses announces.

Anthony takes a final bite of a charred pizza crust and chews it slowly, trying, for the thousandth time, to figure a way out of this mess.

They have been shut away in the cottage for nine days now, J.P., Riley, Anthony and this annoying Little Moses kid, who never stops talking. None of this went according to plan. They were supposed to harass Sam Lee, get him riled up to look like a crazy Chinese guy, film him screaming, then knock him out. Post it on social media as a warning to good American citizens: protect yourself from these infected foreigners.

But then this Moses kid took off running, and J.P. chased after him and Riley freaked out — trigger-happy Riley — and pulled the pistol and shot Lee then dropped the gun and ran. Anthony had to stomp on Lee two or three times to make sure he didn’t chase them, then retrieve the gun and race into the woods. They got 12 seconds of video before all hell broke loose. The whole thing was a bust.

And now they had an eight-year-old kid who they couldn’t set free, because he’d tell the cops everything.

“We don’t care if you want to go home,” Riley says, trying to sound fierce. “If you don’t shut up, you’re never gonna see your mommy again.”

“I am not scared of you! I am Flash!” Little Moses says.

J.P. rolls his eyes. “Why does he keep saying that?”

Anthony checks his watch. It’s 6 p.m. He flicks on the small TV to the local news. The other two men quiet.

The lead story is about a barber who is refusing to close his shop, and other small businesses that are following his lead, defying the statewide orders to shelter against the virus and opening up to customers instead.

After that, there is an update on their case.

“Police are still searching for clues to the shooting of a local man and the kidnapping of a boy who lived with him…”

Little Moses sees the image of Sam Lee above the shoulder of the newscaster.

“Mr. Sam!” he yells.

“Shut UP!” Riley says.

“That is bad thing to say! You not supposed to say that!”

“Oh…shut…UP!”

Riley comes after Little Moses with his fist cocked, but Anthony kicks his arm away.

“Oww! Jesus!” Riley yells. “What the hell, Anthony?”

“You think beating down an eight-year-old is gonna solve our problems?”

“Hey, I’m not the one who said ‘Screw it’ when we saw the kid! I said ‘abort!’”

“And I’m not the one who had to play Rambo!” Anthony screams. “Before you shot the Chinaman, the worst we would have faced is assault. Now you’re looking at attempted murder, deadly weapon, illegal possession, who knows what else they’ll throw on there. Goddamn it, Riley! I’m not going down for 20 years because of your stupidity!”

They stop yelling long enough to hear the newscaster say, “Earlier today, we spoke with Sam Lee, who is out of the hospital…”

Suddenly, Sam is on the screen, his left shoulder bandaged and in a sling.

“I want to say to the men who assaulted me and took Little Moses, bring him home,” Sam says. “Please. Whatever hate drove you to attack me, he’s a child, an innocent bystander. He doesn’t deserve this.”

The camera moves over his shoulder to show Rosebaby standing on the steps, wiping her tears.

“Mama!” Little Moses yells.

“Shut it off!” Riley yells.

“I want my Mama!”

“SHUT UP!” J.P. screams.

J.P. smacks Little Moses in the face and the boy howls. J.P. grabs him and shoves him into a closet, then slams the door.

“I can’t take this kid!’’ J.P. yells.

“Holy crap, J.P.” Riley says. “I thought you were gonna kill him.”

“Quiet!” Anthony yells.

On the TV now is a police chief, followed by a doctor, both encouraging citizens to report any sightings of Little Moses, and a hotline number to call in any clues.

“Nobody is killing that kid,” Anthony says, quietly. “You don’t have all these people on TV for a missing black boy. No, sir. There’s something else going on here.”

He flicks off the TV.

“We mighta just found a way out of this.”

Riley looks at J.P.

“What?” they both ask.

Anthony grins.

“Money,” he says.

AVA PUSHES her grandmother’s wheelchair down the driveway and into the street. It’s late spring, the air is crisp and the trees are in full bloom.

“On a beautiful day like this,” Ginger says, “you can almost forget the world has gone to crap.”

Ava smiles.

“I’m really glad you came home, Grandma,” she says.

“Well, thank you,” Ginger says. “It beats dying in some smelly hospital. Yuck.”

She reaches back and pats Ava’s hand.

“You know, sweetheart, your Mom told me about that boy you kissed.”

Ava blushes.

“You should have told her the minute you found out he was sick—”

“I know, Grandma—”

“But…”

Ginger turns her head to let Ava see her red-lipstick smile.

“But a little kissing isn’t a terrible thing. I did plenty of that when I was your age.”

“God, Grandma, gross.”

“What do you mean, gross? You think I had this old wrinkled face back then? You think the boys I kissed looked like Ricketts from the cider mill? Oh, no, no. They were strong and handsome, like your boy…what’s his name?”

“Troy.”

“Troy. Ooh. A strong name. Like a Greek god.”

“He’s not talking to me anymore.”

“Why not?”

“I don’t know. He just stopped calling.”

“The hell with him. He’s not worthy of you.”

“Grandma! You just called him a Greek god.”

“I changed my mind.”

“Why?”

“Someone treats you bad, he’s dead to me.”

“Grandma!”

“Well.” She smacks her lips. “That’s how I am.”

She pats Ava’s hand again, and this time Ava grabs her fingers and squeezes them tight.

“Grandma?”

“Hmm?”

“Is anything going to be the same again?”

“How do you mean, dear?”

“I dunno. We’re not going back to school. My senior friends aren’t even getting a graduation. There’s no prom. All the summer jobs are gone. The malls are closed. The movies. Dad works every day, dressed like he’s going to war or something. Nobody trusts each other. Nobody wants to get near anybody. Nobody wants to hug anymore. Or have a party. Or kiss…”

Ginger nods silently. They turn a corner by a large hickory tree.

“You know, Ava,” she says, “when I was very little, we were in the war. Every family, it seemed, had someone who was fighting overseas. Here at home, you weren’t allowed to buy more than a certain amount of things.”

“Like what?”

“Oh, lots of things. Gas. Food. Meat. Sugar. Tires for your car. Even clothes.”

“Why?”

“They needed those things for the soldiers. I remember going with my brother every week to collect cans. We went up and down the street. We looked in the alleys. Whatever we got, we turned in.”

“What for?”

“Well, now I know it was to make things like guns or tanks. But back then, it was just something we did because we were supposed to. That’s what Americans did. And that’s my point. Because I grew up in it, I thought that’s how life was. I didn’t see it as a sacrifice. We only could eat a certain amount? So what? We only could use this or that? So what? Everyone did it, and we were in it together.”

Ava thinks. “So is that what we’re doing now?”

“It’s what we should be doing now,” Ginger says. “But we’re spoiled. We’ve gone soft. Nobody wants to go without toilet paper. Toilet paper! My God. There are places in the world where they wipe their asses with a leaf.”

“Grandma!”

“Well, it’s true.”

They move along silently. The sun ducks behind a thin cloud, then reappears, warming them. Ginger looks to the sky. She closes her eyes.

“I almost died,” she whispers. “I was ready to go. I don’t know how your father saved me, but he did.”

Ava starts to cry. Ginger turns in her chair.

“What is it, sweetie?”

“I’m just happy you’re OK,” she says.

“Ah.”

Ginger reaches up and pats Ava’s elbow.

“There’ll be other boys to kiss one day,” she says. “I promise.”

LILLY FINISHES her prayers. As she rises from the pew, she turns to see Rosebaby sitting in the last row of the sanctuary, her head bowed, her hands clasped together. It is Thursday morning. They are the only people in the church.

Rosebaby looks up and wipes a tear from her cheek.

“How are you, honey?” Lilly asks. “Is there any news on Little Moses?”

Rosebaby shakes her head.

“Every day I ask God to return him to me,” Rosebaby says. “But today I make a change. I ask for something else.”

“What did you ask for?” Lilly says.

“Someone to go find him.”

Lilly is unsure how to respond.

“May He grant you that wish,” she finally says.

“Where is the Pastor?” Rosebaby asks.

“He is home,” she says. “Resting.”

Rosebaby rises. She pulls a scarf around her nose and mouth. Lilly, who has a facemask hanging around her neck, lifts it into place.

“I can’t help but look at people in these masks,” Lilly says, “and feel like everyone is about to rob a bank. I know it’s silly. Such different times—”

“Miss Lilly?”

“Yes?”

“Pastor did nothing wrong. He gave us a chance to pray together. Surely God will not punish him for that.”

Lilly is taken aback. “Thank you for saying that, Rosebaby.”

Winston has been sick for three days now. He came home one afternoon from the shelter and his eyes were red and he went right to sleep. After that, he began to run a fever and immediately banished himself to the basement, where he remained, sleeping on a couch and taking his food from the top of the steps. Lilly sent the children to stay with her mother, because she worried they would touch something Winston touched or sneak downstairs to see him when she wasn’t looking. Their oldest, Todd, has more curiosity than discipline. And the twins, Devon and Didi, are only nine and wouldn’t understand why their father was no longer kissing them goodnight.

“Will you tell Pastor that I am praying for him, Miss Lilly?” Rosebaby says.

“Of course.”

“Have you spoken to Dr. Greg?”

“No. I’m sure he is so busy—”

“You should talk to him, Miss Lilly. He can help.”

“All right. Thank you.”

Rosebaby turns to go.

“I’m so sorry, Rosebaby,” Lilly blurts out. “For what you must be going through. Here I am talking about Winston, and you, not knowing where your boy is. And Sam being shot. All of it. It’s so terrible. I don’t know what’s going on. This world. This disease. It’s a tragedy.”

Rosebaby looks away. Her voice softens. “Do you know, in Haiti, I once saw a man run into the street and get hit by a truck? He was very thin and very poor and he had dropped a mango and it rolled away. He was chasing it. I thought to myself, ‘Did he not see the truck coming? Or was he so hungry that he took this chance?’”

“Tragedy is everywhere, Miss Lilly. My Moses is alive. I know it. I feel it in my soul.”

She walks to the door and holds it open.

“Let us see who the Lord sends us.”

OLD MAN RICKETTS carries a carton of bread loaves from his car to the cider mill entrance. It is not even noon, and there’s already a line of people, spaced six feet apart, wearing masks, some wearing goggles.

“You doing roast beef today, Mr. Ricketts?” one customer asks.

“Yeah, yeah, we got roast—”

He stops. By the door, he sees three men in overcoats and suits. He knows right away they’re not there for sandwiches.

“Can I help you men?” he says, approaching.

They look at the customers, then at each other, as if hesitant to speak out loud.

“Come around back,” Ricketts says, not even waiting. “I knew you were the feds.”

A few minutes later, the men are grilling him about Buck and Daniel and the guns and the incident at the capitol. As Ricketts measures his answers, he can tell they’re really only interested in one thing: finding Little Moses.

“Look, I know the kid, he’s a good boy,” Ricketts says. “Never says a bad word. Never has a bad day, as far as I can tell.”

He leans in. “But you gotta tell me why the federal government is looking for a little Haitian kid. I know police work. A missing person is left to city or state. Unless you’re trying to deport him.”

One official looks at the other, then says, “We’re not trying to deport him. We think he can be of great help in this pandemic.”

Ricketts is surprised. “Little Moses?”

The other man interrupts. “We need to talk to your grandson.”

“I understand. Like I told you, when he gets back, I’ll call you guys. I don’t know where he is right now. He’s 18. You know kids at 18. They don’t exactly punch in and out.”

A few minutes later, the men leave. Charlene appears at the kitchen doorway.

“What did they want?”

Ricketts rises and puts his hands on his lower back, then bends forward and winces.

“Are you OK?” Charlene says.

Ricketts grunts and mumbles, “Yeah, yeah, I’m fine” and passes her heading to the steps. He climbs them slowly. When he reaches the upper bedroom, he doesn’t knock. He kicks the door with his boot and it bangs against the inner wall.

Buck, on his bed, looks up in surprise.

“Now you and me are gonna talk,” Ricketts says, “and you’re gonna tell me every goddamn little thing.”

“WHAT DID I tell you?” Anthony howls. “What did I tell you?”

The three men, Anthony, J.P. and Riley, are on the floor of the cottage, drinking beers. On the TV screen, a reporter is standing in front of a large building.

“The missing boy in the recent shooting/kidnap event is, according to sources, being pursued by federal authorities as well as local law enforcement. It is believed the child may have information regarding the coronavirus that is important in understanding how to combat it.”

“What the hell does that mean?” Riley asks.

“It means he’s worth something,” Anthony says. “If this kid has something to do with curing Chinese virus, you know how much people will pay for him?”

“Hell, yeah,” J.P. says, sitting up. “You could have a bidding war. Sell him to the highest country.”

“Yeah, let’s have a bidding war,” Riley mocks. “From the woods.”

“Shut up, Riley,” J.P. snaps. “When are you gonna change that t-shirt? You smell like a year’s worth of jock straps.”

“Kiss my ass,” Riley says.

“Shut up, both of you.” Anthony moves to the table. “The heat just went up on this kid. We gotta get a ransom note out there.” He turns. “J.P., get him out of the closet.”

“Let Riley do it. I can’t stand that little bastard. He never shuts up.”

Riley rises. “I’ll get him.”

He opens the closet door. Little Moses is on the floor. He has three hangers in front of him that he has twisted into toys.

“Get out here,” Riley says.

“I am hungry,” Little Moses whispers.

Riley yanks his arm and pulls him out.

“He sounds like crap. Maybe we should be feeding him more.”

“He had a pizza slice this morning,” J.P. says.

“Hey, kid, can you write?” Anthony says.

Little Moses looks around. The room is very messy. Pizza boxes are everywhere. And beer bottles. There is a gun, like he sees in the movies, leaning against the wall.

“Yes, I can write.”

“Come here.”

Twenty minutes later, Moses has written the letters the tall man told him to write. He doesn’t know what the words mean, but the tall man seems satisfied.

“Here, you can have some orange juice,” Anthony says, handing him a bottle.

“Thank you,” Little Moses says.

J.P. snickers. “The kid is thanking you. You snatch him, he thanks you. Unbelievable.”

“It’s not the kid’s fault,” Riley says. “He just happened to be there.”

“Yeah, and he ran.”

“Yeah, and you chased him.”

“Yeah, and you shot the chink.”

“I said, shut up, both of you!” Anthony bangs a fist. “We’re gonna post this note and we’re gonna get paid and then I am getting as far away from you two morons as is humanly possible.”

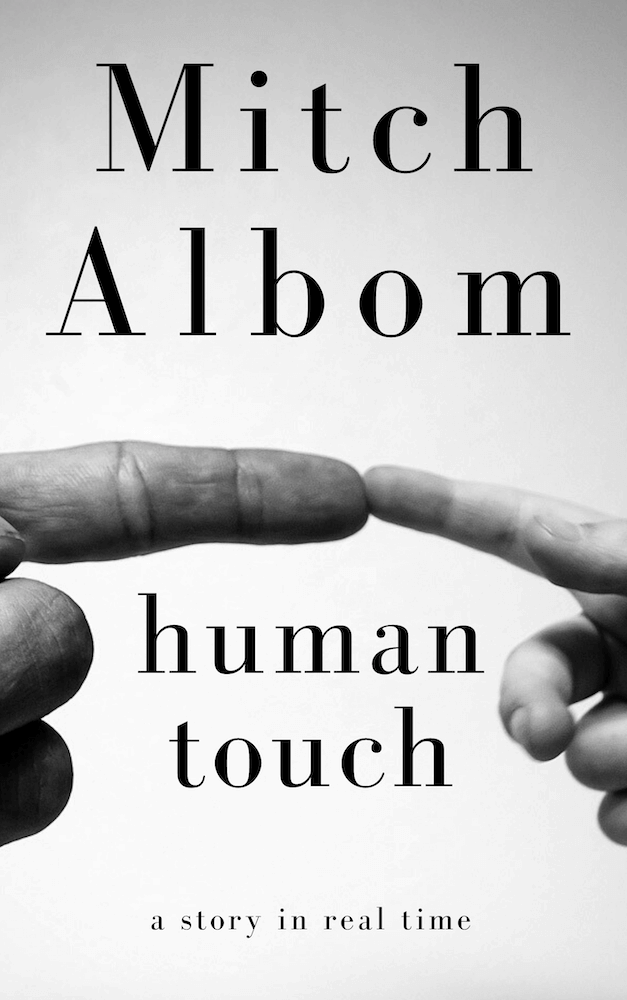

He positions Little Moses holding the ransom note. He holds up his phone to take a photo.

Little Moses actually smiles.

“Jesus, this kid,” Anthony mumbles.

He takes the picture. He checks it. The ransom note is legible. He turns to the other men.

“Pack up,” he says. “We gotta be out of here first thing in the morning.”

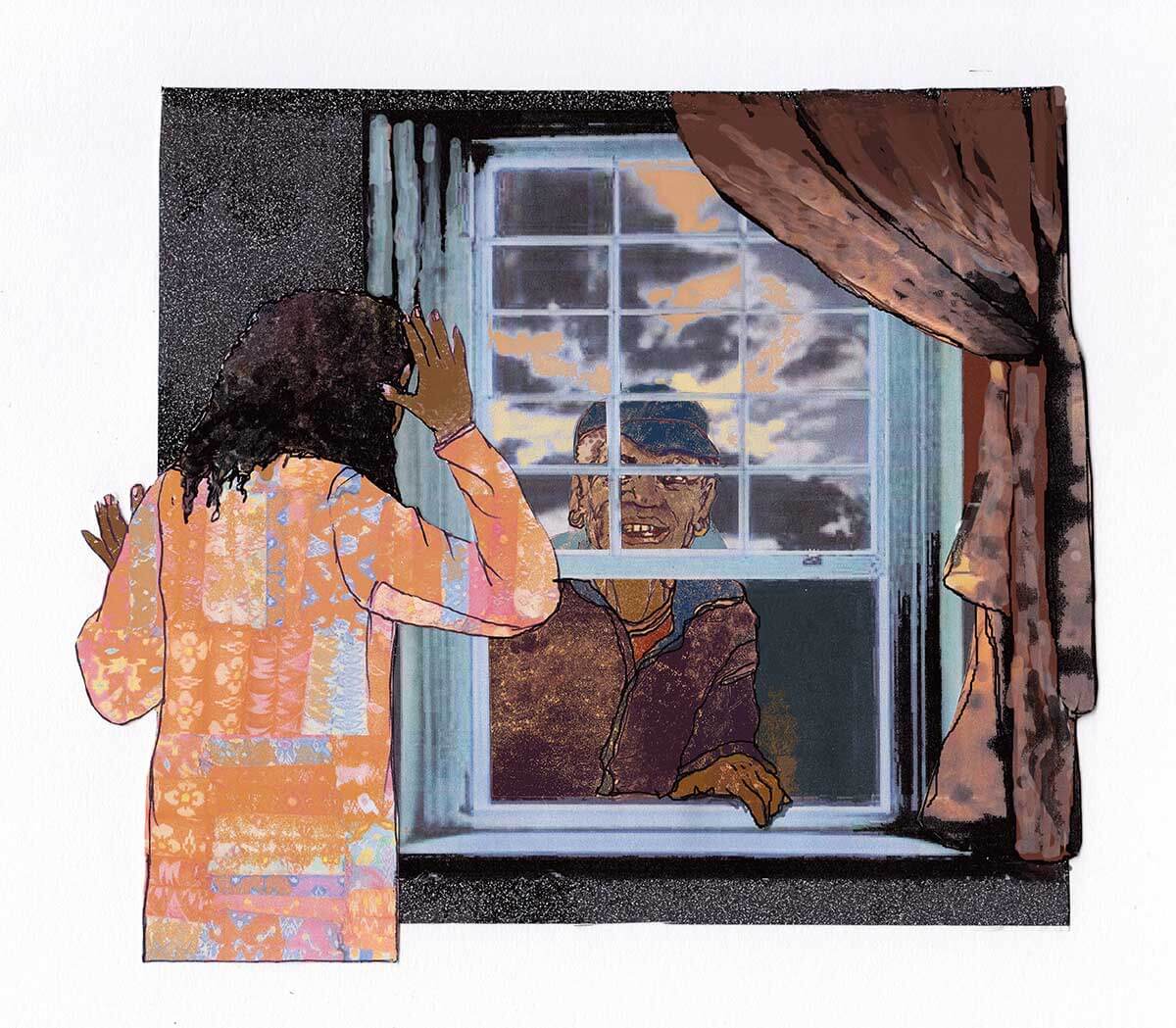

THAT NIGHT, a big storm hits southern Michigan. The crackle of thunder jolts Rosebaby from her sleep. She hears the rain hammering the roof and the wind rolling the drops against her window like fingers on a conga drum.

She tries to go back to sleep, but she hears the window noise again – only this time it is not the rain, but a tap. She opens her eyes and waits. There it is again. A minute later, again.

She rises, slowly. She and Little Moses sleep on the first floor, in the guest room nearest the laundry. The windows look out on the backyard. A flash of lightning illuminates the room and Rosebaby counts the seconds until the ensuing thunderclap. One. Two. Three—

Varooom.

That means the storm center is less than a mile away.

She reaches the window near the desk. It is pitch black again. No moon on this night. She hears a tap on the pane. Her pulse quickens. As she leans forward, the lighting strikes and she jumps back in horror.

A man is standing on the other side.

The man pushes the window up from the outside. It’s open? Why is it open? Rosebaby feels powerless to move. She edges her hand towards a desk lamp, and as the man leans his head through the opening, with everything she has, she wills her fingers around the base and swings it towards him.

Smack! The man’s hand catches the lamp before it strikes him, accidentally pressing the switch which turns the bulb on.

“You!” Rosebaby shrieks, seeing his face.

The Haitian man in the cap and earring returns the lamp to the desk and offers a gap-toothed smile.

“Li lè pou m’jwen pitit gason mwen an,” he says.

“It is time to find my son.”

End of Chapter Seven

Pay it Forward

If you're enjoying "Human Touch" so far, would you consider, if you're able, adding a human touch of your own by donating any amount to help my hometown city of Detroit battle the wave of coronavirus that is overwhelming it? Our citizens are struggling - and dying - in high numbers. "DETROIT BEATS COVID-19!" focuses on first responders, seniors, poor children and the homeless.

Thanks, as always,

Don't miss the next chapter!

Click here to get notified when the next chapter is available, or subscribe to the newsletter to get it early!

Listen to the audio

Available for free exclusively at Audible.com. Read by Mitch Albom and a special guest!

Download as an e-book

Please consult your specific device’s manual for how to add one of these to your library.

Recent Books

Finding Chika is a celebration of a girl, her guardians, and the incredible bond they formed—a devastatingly beautiful portrait of what it means to be a family, regardless of how it is made.

A sequel to the bestseller The Five People You Meet in Heaven, Eddie’s heavenly reunion with Annie — the little girl he saved on earth — is an unforgettable novel of how our lives and losses intersect.

The Story Continues …

Chapter Eight

Read Now

About the Series

Chapter One

Read Now

Chapter Two

Read Now

Chapter Four

Read Now

Chapter Five

Read Now

Chapter Six

Read Now

Chapter Seven

Read Now

There's always more to read with Shelved...

Sign up for Mitch's free newsletter. Non-spammy. When there’s something great to share, we’ll send special updates your way. Exclusive items like excerpts from a new book, signed book giveaways, event alerts, and more. Still need more? Get familiar with Shelved here.