He was the father who chased runaway rabbits in the middle of the night (in his pajamas), who let his kids throw up on him, read over their homework, taught them to drive, attended every major event of their lives — and their kids’ lives — and who’d fly across the country if there was a whiff of trouble.

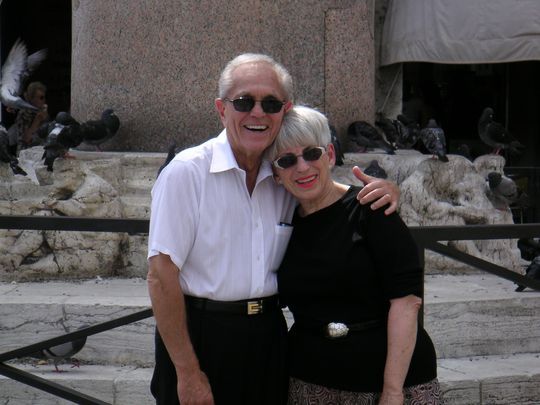

A man who relished a long drive, a good cup of coffee, and saying, “I love you, kid.” A contract negotiator so well-regarded by the firms he dealt with, that they often refused to negotiate until he was in the room. And a husband so dedicated to my mother Rhoda — the only woman he had ever loved, kissed or dated — that our next-door neighbor used to crack, “When I die, I want to come back as Ira Albom’s wife!”

We used to beg our parents to tell us a romantic story of how they got engaged, but they shrugged and said it was never a question. My father stepped in at age 16 when my mother’s father died of a heart attack, and he essentially became the man of my mother’s house, raising her kid brother and tending to my grandmother, who fell into depression.

The closest we came to a romantic anecdote was the day my dad drove over with the ring, and my mother was watching out the window, her brother beside her. My dad pulled up, then realized he’d left the ring at home. So he drove back to get it.

“I TOLD YOU NOBODY WOULD EVER MARRY YOU!” my uncle screamed, laughing.

Not exactly Romeo and Juliet, but there it is.

Ira Albom led by example

Since my father passed away, I have been amazed to hear stories from around the country, tales of meetings, conversations, lunches, a long walk, in which my father dispensed wisdom and patient advice, and said things these people remembered decades later. Many of them had only met my father a few times. But he had that way about him, as if he’d lived many lifetimes, and effused the quiet confidence that comes from knowing what will pass and what won’t. A childhood friend of mine said at his funeral, “Mr. Albom was always a grown-up.”

That’s true.

But while his protective shadow covered many, his physical imprint fell on me. Anyone who saw us together knew I came off his assembly line. From the Ira Albom catalogue, I inherited the standard model big ears, large chin, crooked sinuses and unfortunate underbite.

I also, happily, inherited his deep voice. As the years passed, and I made it through adolescence, I began to sound more and more like my Pop. Sometimes I would call him at work and he would pick up the phone and say “Albom speaking,” and I’d say “Albom speaking” — the same timbre and pitch — and he’d say “Very funny,” and I’d say “Very funny,” and he’d say “Knock it off,” and I would stop.

Because you did not push my dad.

Everybody knew that. I am not ashamed to say my father disciplined us. In the 1960s, the parenting manuals didn’t forbid spankings, and I had plenty. But they were only and always for the same sin: disrespecting my mother. And not once did I feel afraid, scarred, or that the hand lightly whacking me contained anything but love. Heck, he used to say it between spanks: “I…am…doing…this…because…I…LOVE…YOU!”

The truth is, while my creative hurricane of a mother taught me all the things I could be, my father taught me all the things I should not be.

By example, he taught me not to be disrespectful. Not to be unethical. Not to disregard what the other party wanted. Not to be a fool. Not to be a drunk. Not to be impolite. Not to lose your dignity.

Once, when I had just started college, the company he’d worked for 19 years abruptly fired him — one year shy of vesting his pension, leaving him practically at square one. We later learned the reasons were the kind of discrimination you could sue for now, but my father never complained, even though we’d just moved to a new house, and who knew how we would pay for it?

As a bone, the company offered him a spare office for a few months from which he could make phone calls. I was shocked when he chose to take it. “Won’t you be embarrassed?” I asked.

He calmly replied, “Nobody can embarrass you unless you let them.”

And so every day he put on a suit and tie, drove me to my summer job at a factory, then went in to his old workplace, said hello to people who used to work for him, and spent the day in that spare office looking for new employment, because taking care of the family was paramount.

Not to lose your dignity. Not to bend your principles. Not to be cruel. Not to be unforgiving. Not to act like small things don’t matter — birthday calls, congratulations calls, condolence calls.

Anniversary calls.

Christmas Eve. I need to make a phone call.

I can’t.

The true meaning of a life together

When I watched my father laid in the earth, finally united with my mother, I felt a mix of anguish and relief, because for nearly three years the world had seemed unbalanced. My dad was here. My mom was gone.

When I watched my father laid in the earth, finally united with my mother, I felt a mix of anguish and relief, because for nearly three years the world had seemed unbalanced. My dad was here. My mom was gone.

He shriveled without her. He was not in good health when she died (she had a stroke, then he had a stroke, because, you know, they had to do everything together). And as the years passed, he slowly lost mobility and communication, ending with a bedridden, hollowed body and a few grunts of “Hi” and “Love you.”

I could see how he was ready to be with her, no matter how much we wanted him with us. He often told me, “Mitchie, I’ll stay until 90, but that’s it.”

He died 18 months shy.

It was the only promise he didn’t keep.

That’s OK. I realize now that mourning the two of them feels more natural. And what a fortunate feeling that is in this world.

I had two parents. Two great parents. They got married and stayed married and valued family and children and a sense of home. And it’s not a coincidence that their kids and grandkids now do the same.

I’ve had to think a lot about death this month. And I’ve made an observation. When a loved one dies, they leave in two ways:

They leave the world.

And they leave themselves behind.

This is the self my father left behind: a role model that — if I don’t always measure up to — I can always look up to. A role model of warmth, devotion, compassion, humility, work ethic, family ethic and dedication to the one you love.

Sixty-seven years ago in a Brooklyn restaurant, two people came together, and their love ultimately led to the words being written here about them.

I need to make a phone call.

I can’t.

But I can do something: I can imagine them together, hugging and pinching each other, as they were known to do. There is comfort in that. Even if it’s not on this earth.

Happy Anniversary, Mom and Dad. Happy Christmas Eve, everyone else. If you are lucky enough to still live in the world of parents, hold them close. Hold them as if you’ll never let them go.

Contact Mitch Albom: malbom@freepress.com. Check out the latest updates with his charities, books and events at MitchAlbom.com. Download “The Sports Reporters” podcast each Monday and Friday on-demand through Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Spotify and more. Follow him on Twitter @mitchalbom.

0 Comments